by MARGO SNIPE

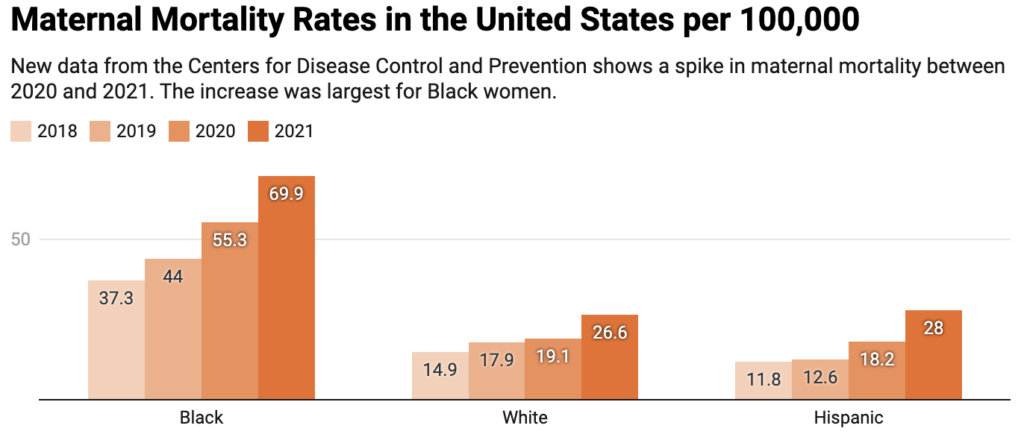

Black women had the largest rate increase between 2020 and 2021, new data from the CDC shows. Maternal and child health experts point to systematic racism as the root cause.

This article was originally published by Capital B News, a Black-led, nonprofit news organization reporting for Black communities across the country.

The coronavirus exacerbated the effects of medical racism already baked into the United States healthcare system, leading to a spike in Black maternal mortality rates between 2020 and 2021, new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveals.

The recent statistics, though bleak, come as no surprise to maternal health experts, who say the disparities have persisted for decades.

“This isn’t a new problem,” said Tiffany Green, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison focused on population health and obstetrics and gynecology. The disparities have been well-documented for many years, she said.

In 2021, more than 360 Black women died of maternal health causes across the country, according to the CDC, up from just over 290 in 2020 and more than 240 the year prior. The spike amid the coronavirus pandemic is likely due to a combination of factors, ranging from infection by the virus itself to medical racism.

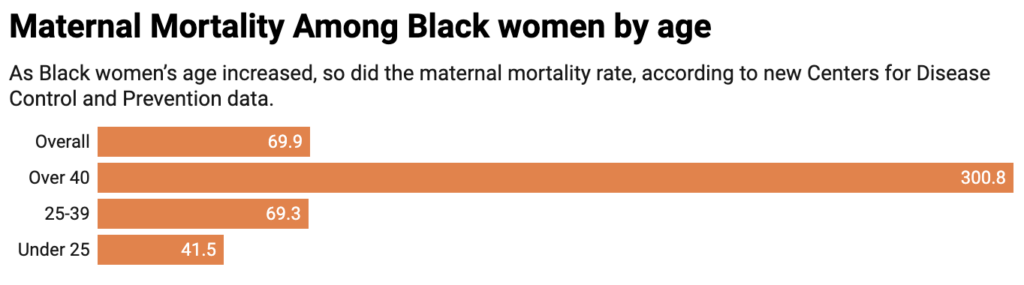

As women’s age increased, so did the maternal mortality rate. For Black women over 40, the rate was over 300 per 100,000 births, compared to 42 per 100,000 for those under 25.

Despite advancements in medicine and technology over the years, the racial gap in who is suffering the most severe consequences of childbirth is growing, and most Black maternal and child health experts point to systematic racism as the root cause. Inequities in access to quality healthcare before, during and after pregnancy, as well as provider bias during labor and delivery, contribute to the dismal outcomes. And, the “weathering” effect that exposure to discrimination has on Black people’s bodies over a lifetime, which can break down a mother’s body prematurely, is also linked to the high death rates.

“Maternal disparities have little to do with race, and more to do with Black women’s experience of racism. There is nothing inherently wrong with Black women.

Inas-Khalidah Mahdi, the National Birth Equity Collaborative

That, combined with COVID’s disproportionate impact on Black Americans, drove the spike, experts say.

“We cannot separate maternal mortality and maternal morbidity from the inequitable systems that they arise from,” said Inas-Khalidah Mahdi, the vice president of equity-centered capacity building at the National Birth Equity Collaborative. For decades, she said, medical professionals have wrongfully blamed Black women’s behavior and genetics for their poor outcomes, but evidence shows “maternal disparities have little to do with race, and more to do with Black women’s experience of racism.”

She added, “There is nothing inherently wrong with Black women.”

The spread of COVID-19 decreased the quality of maternal healthcare for everyone across the country, said Mahdi, so for those who already had issues accessing high quality care, the impact of that care being further reduced had a significant effect.

Hospitals began to limit the number of people in the labor and delivery unit to slow the transmission of the coronavirus, which meant Black patients often weren’t allowed to bring in their support teams, including their husbands, partners, family members or birth advocates.

“We know doulas and midwives are literally saving lives within our broken system,” said Jennie Joseph, a British-trained midwife and founder of Commonsense Childbirth Inc. Without them, she said, there are few people advocating for the patient throughout labor and delivery and improving the quality of care, making childbirth increasingly dangerous.

While the virus was spreading nationally, Joseph said, outcomes at her birth center in Winter Garden, Florida, continued to excel as in years prior. The team pivoted to telehealth and quickly learned that patients did not want to be on video, so they began to offer phone services. It was apparent that expecting parents were more comfortable texting and hopping on a phone call than being on camera. Suddenly, she said, they were sharing every little detail, making it easier for the team of providers to offer the best care.

“We opened a whole new community through the phone that made everybody feel safe,” Joseph said. Her birth center did not see the same racial disparities that the new CDC data shows. In 2020, the center cared for over 480 patients, had no deaths, and only one preterm birth. Joseph says it supports evidence that the system of obstetric care in hospitals is failing families, especially Black people.

“This is structural,” she said. “These are preventable harms.”

Last year, Joseph was recognized as one of Time magazine’s Women of the Year.

As the pandemic progressed, it also became clear that Black people were more likely to be exposed to the virus as well as suffer the most severe complications, data shows. That may have bled into birth outcomes, said Green, the professor.

“COVID can be even more severe among vulnerable populations, including pregnant folks,” she said, and “a lot of pregnant people were not getting vaccinated.”

Green noted the lack of representation of pregnant people in vaccine clinical trials and the widespread presence of misinformation around how safe and effective vaccinations were throughout the rollout as factors contributing to the slow uptake of shots among those who were pregnant.

Still, the virus itself may not tell the full story of why Black people had the largest spike in death.

“It is not fully clear where these changes are coming from,” Green said. “It will take some time to understand.”